Washington The vigorous federal push to build interstate highways has been replaced by funding speed bumps, requiring states to negotiate difficult finance issues and demonstrate that projects are worth billions of dollars before construction can begin.

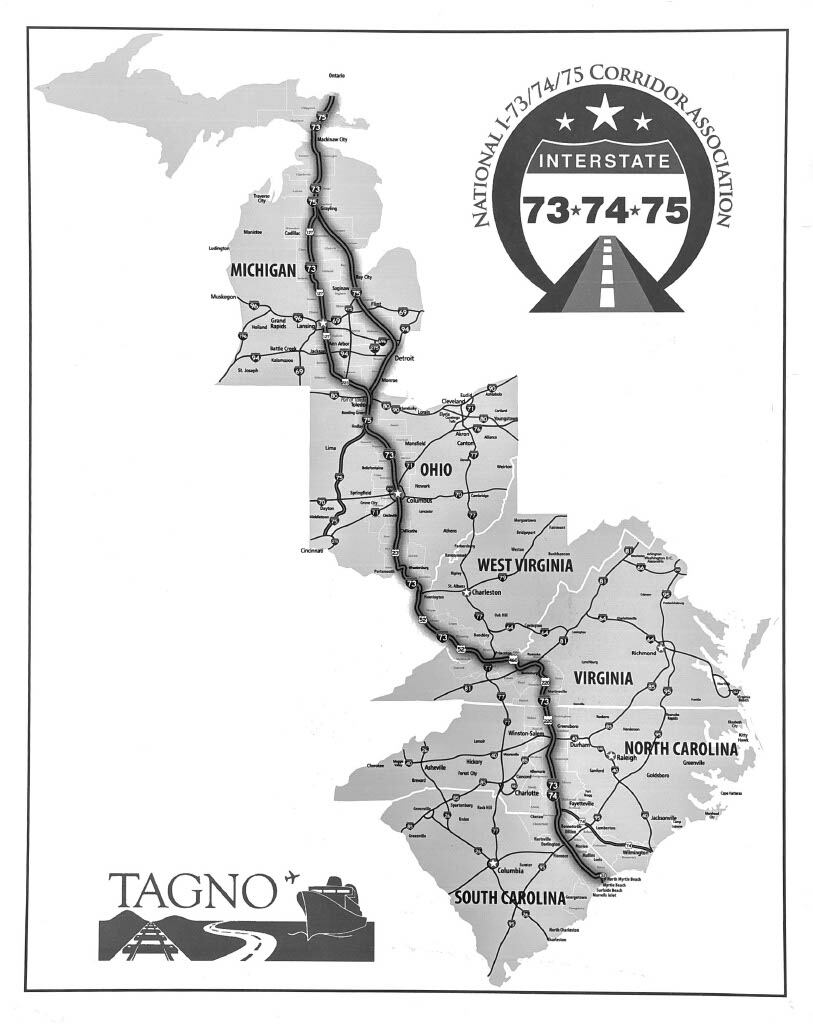

Planners in six states have been working for decades to build a new interstate highway that would connect Michigan to South Carolina via Ohio. The task is made more difficult by the reduced funding picture. These planners are tying together planned construction and existing roads to create a transportation corridor that has the potential to transform regional economic development.

Chronic shortages in the Highway Trust Fund are a major cause of the change in the financial picture.While construction costs have skyrocketed and fuel efficiency has decreased per-mile tax collections, federal fuel taxes have not been raised since 1993.

In order to maintain transportation initiatives, Congress must frequently transfer funds from general revenues due to the fund’s ongoing deficits. States’ approaches to large interstate projects have been drastically altered by this financial crunch.

There is currently a significant structural imbalance that causes difficult decisions regarding which projects receive federal funding, with transportation spending averaging around $80 billion annually and revenue, excluding General Fund transfers, lingering around $43 to $43 billion annually.

In order to determine the viability and potential routes for a new Interstate 73 corridor that would link underdeveloped areas of the state to a nearly 1,000-mile transportation network, Ohio is presently doing a $1.5 million feasibility study.

According to advocates working on the multi-state project, the Ohio Department of Transportation study, which is expected to be finished by the end of 2026, reflects broader changes in how major highway projects are funded in a time when states don’t want to pledge state money until there is federal money and the federal government doesn’t want to fund until they have state buy-in.

Study will guide scarce funding allocation

A crucial first step in deciding whether Ohio should invest in the Interstate 73-74-75 corridor, which would connect the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, via Ohio, West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina, is the ODOT feasibility study.

The study’s main goal, according to documents from the Ohio Department of Transportation, is to present an unbiased, open analysis of what it would take to create I-73, stressing that this is purely informative and not a commitment to build the interstate. The study provides information to state decision-makers so they can act appropriately and aids in identifying the best ways to distribute limited funds.

Mostly following U.S. Route 23, the Ohio portion of the proposed interstate would travel south from Toledo through Columbus and all the way to the Kentucky/West Virginia border close to Chesapeake, Ohio.

According to ODOT, the study’s conclusions will be used to guide possible routes, determine the project’s future, and allocate state funds.

Funding challenges reflect national infrastructure reality

According to Jimmy Gray, executive director of the I-73, I-74, and I-75 Corridor Association and president of the Myrtle Beach Area Chamber of Commerce, the funding issues are a reflection of broader shifts in federal infrastructure investment, as the government of the United States is no longer promoting the construction of interstate highways as it was in the 1950s.

“There are times when we have to choose between the two,” says Gray. Until federal funds are available, states are reluctant to pledge state funds. Prior to funding, the federal government wants state support.

Members of the organization tasked with constructing the highway have been meeting with congressional representatives in six states on a regular basis to discuss progress and plan ways to get funds, according to Gray, who claims the idea has been discussed for over 30 years.

Although sections of the road have been designated as priority corridors in each of the six states, progress differs amongst them. With permits authorized by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and right-of-way acquired, South Carolina is shovel ready after completing environmental and permitting studies for its portion.

Gray says, “We’re just waiting on money.” The holdback is that.

Voters in Horry County, South Carolina, approved a referendum that allocated $450 million for the construction of Interstate 73, which is roughly half of the estimated $900 million cost for that segment. This shows the innovative financing options that states are looking into, such as federal grants and local sales taxes.

Congressional support emerges

Citing expanding defense-related firms in the area, U.S. Representative Dave Taylor, whose district would be served by the route, submitted a congressional resolution last month endorsing the development of Ohio’s section.

According to a statement from Taylor, southern Ohio requires infrastructure to support companies like a defense technology corporation constructing an advanced manufacturing plant in Pickaway County to produce military drones and autonomous air vehicles, and a burgeoning uranium enrichment center in Piketon.

According to Taylor, an interstate through southern Ohio would improve our national security due to the numerous important facilities and defense-related businesses along the route, in addition to helping rural towns link to the contemporary economy.

At a recent House Transportation Committee hearing, Taylor asked Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy for support for the project, and Duffy indicated he would be pleased to speak with Taylor about USDOT’s role.

Duffy stated during the hearing that there are far too many underdeveloped towns, the majority of which are frequently rural.

Economic development engine awaits funding solutions

According to Gray, the proposed roadway would reduce the driving time from Ohio to Myrtle Beach by hours, making it more of an engine for economic development than a boost to tourists.

According to Gray, these six states have had significant expansion in both residential and commercial areas. He claims that while interstate highway connectivity is a crucial consideration for businesses when choosing where to locate their facilities, areas without it frequently miss out on prospects for economic progress.

From Michigan’s manufacturing base to Ohio’s defense and technological facilities to the Carolinas’ tourism sector, the corridor would link important population centers and industrial hubs.

Critical bottlenecks drive Ohio s interest

The Transportation Advocacy Group of Northwest Ohio’s executive director, Tom Kovacik of Toledo, has spent 25 years focusing on Ohio’s share. Creating a bypass for U.S. 23 in Delaware, Ohio, where 38 traffic lights in 20 miles obstruct traffic, is a top priority, he adds, in order to remove bottlenecks that restrict free-flowing traffic between Toledo and Columbus.

According to Kovacik, if you’re a trucking firm attempting to get from Toledo to Columbus, you’re stranded in a 20-mile stretch with almost 40 red lights. It’s a logistical nightmare, not an expressway.

The proposed bypass would completely remove the clogged route through Delaware by connecting U.S. 23 to Interstate 71 north of Columbus. Although Kovacik thinks it would be worthwhile, he estimates that any one of the possible routes would likely cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

He claims that many of these distribution hubs are setting up shop in Columbus and Ohio. We recently received a new Intel factory. It’s just outside of Columbus. It’s crucial to take the road from Columbus to Northwest Ohio.

According to Kovacik, he will have achieved his objective of guaranteeing a direct route from Myrtle Beach to Mackinaw, Michigan, once the Delaware bypass is finished. He declared, “I’ll be among the first people on that bypass.”

Rural communities seek economic lifeline

Scioto County engineer Darren LeBrun characterized his region of southern Ohio as being trapped in a black hole, with a dearth of interstate connections impeding economic growth. Although Interstates 71, 70, and 77 encircle the area, there are no direct connections.

According to LeBrun, Portsmouth is a manufacturing-based rust belt town. If there isn’t interstate access, developers will keep looking and we won’t be taken into consideration when they come in to build a factory or large development. For us, it is a handicap.

He stated a large percentage of his county’s citizens drive to Columbus every day, facing 90 minutes to two hours of driving each way, due to a lack of local employment that he believes an interstate highway would address. According to him, an interstate corridor might improve safety and cut that journey by at least thirty minutes.

LeBrun recognized that the project’s enormous scope and cost would necessitate gradual development over many years. Preferred alignments and related costs for each alternative will be determined by the ODOT feasibility study, which will also provide the technical basis required to obtain future financing.

He compared the strategy to the construction of North Carolina’s Interstate 74, which took more than 20 years to finish, and stated that the important thing is to have the plan in place first, after which it can be built in stages.

According to LeBrun, there used to be prosperous shoe industries and steel mills in these areas. We have access to the Ohio River, rail, and physically fit individuals; we only lack the highway. That is the missing component.

Gray is hopeful that the project will eventually be finished in spite of the financial difficulties.

“I am still convinced that this project is essential in all of these corridor states,” Gray says. Because it’s a good project, it will happen.

This story was drafted with assistance from artificial intelligence.

Interstate 73 project faces funding hurdles despite economic potential